Tuesday, April 30, 2019

Vivian Bercovici: The NYT is sorry for its anti-Semitic cartoon, but the problem isn't 'process.' It's hatred of Jews

Vivian Bercovici: The NYT is sorry for its anti-Semitic cartoon, but the problem isn't 'process.' It's hatred of Jews

In the drawing, a Jewish stooge, Trump, is led on a leash by a triumphant dachshund. That's no accident

https://nationalpost.com/opinion/vivian-bercovici-the-nyt-is-sorry-for-its-anti-semitic-cartoon-but-the-problem-isnt-process-its-hatred-of-jews

Sent from my iPhone

Saturday, April 27, 2019

Irish Monasticism

The ‘Catalogue of the Saints of Ireland’ divided the Saints of Ireland into three orders. The first contains all those bishops deemed to have received their ministry from St Patrick. The second lists monks who had received their ministry from Britain. The third consists of hermits. But the document is of 9C or even 10C and is clearly designed to boost the prestige of Patrick and his bishops over against the monks and hermits. But these orders were not consecutive but contemporary one with another and should be dated to the 6C. This century was one of great expansion which saw not only bishops, but monks and hermits, spreading everywhere in Ireland. The result was that the monasteries became the de facto centres of the church. Monasticism, with its multiple forms, had great appeal because its adaptability.

The traditional founder of the monastic movement is said to have been St Finnian of Clonard (548) who had received training in Wales. He was undoubtedly a great founder and teacher. But there were many before him. Patrick’s relation to the monastic life is unclear though interesting. Some deny he founded any monasteries on the grounds that bishops came first and monks later. Yet St Patrick was firmly in favour of the dedicated life; he refers to it four times. Most explicit is his statement that, ‘The sons of the Irish and the daughters of their kings are monks and brides of Christ’. But even if this only referred to individuals not communities – and this is not clear- for a bishop in the 5th C to be so positive is unusual. His companion St Tassach (470), founder of the church at Raholp just 2 miles from Saul, is said to have spent 7 years on Rathlin O’Birne off the coast of Donegal with other hermits before 500. If so this is of extraordinary interest. St Enda (530) spent many years first as a hermit, founder of a monastery and teacher of many on Inishmore, the main island of Aran Co Galway. St Donard (507) at Maghera Co Down is said to have had a hermit’s cell on top of Slieve Donard in the Mountains of Mourne. St Forthchern (5C), who is said to have been a bishop and then a hermit in Meath, may have been the teacher of Finnian. St Buite (523) founded Monasterboice in Co Louth. St Senan (546) evangelised West and South Clare and he and his disciples founded many places around the Clare coast and on the islands of the Shannon estuary. There are also several remarkable women saints from the early period, St Gobnait (5C) at Ballyvourney (Co Cork), St Arraght (5C) at Killaracht and Monasteraden (both Co Sligo), St Monnina at Killevy (Co Armagh) (517), St Brigit (524) at Kildare, St Bronagh at Kilbroney, Rostrevor (Co Down) and St Ita (570) at Killeedy (Co Limerick).

St Columba (597) was perhaps the most prolific founder of monasteries of all. Born at Garten in Co Donegal, he was of royal blood, of commanding stature and evidently of great charisma. He eventually left Ireland for Scotland where, from this base on Iona, he evangelised among the Picts. His ‘Life’ written by St Adamnan gives a vivid picture of an Irish saint and monastery.

In Ireland the church was always the local church. There was nothing else. The local tribe was the point of meeting one with the other, and the number of tribes was enormous, though they might be joined up in little kingdoms or bigger ones. When the tribe responded to the Gospel, an enclosure would be set aside, with boundaries and ‘termon’ crosses, sometimes with a ditch, sometimes with a wall, clearly marking out to everyone that the area was sacred. Within it a tiny church of wattle and daub would be built. That would not take long.

In many places there seems to have been no shortage of aspiring monks. As for sites, as one travels to the places they chose one is amazed by the astonishingly beauty of the places they picked. In particular the sea islands (particularly off the West coast) and the many Lough Islands furnished such places in abundance. Even today travelling throughout the island the memory of the founding saints is singularly well preserved, though often there is little detail. Something is known of some 250 from this early period but this does not include many more, without number, whose names are hardly known, were never recorded, or which have become lost.

Whoever they were, bishops, monk or hermits (and some bishops were monks or even hermits) some founded several churches. 4000 is the estimated overall number. Of course nothing survives of the perishable materials used. But where wood was plentiful, churches were also made of planks; or if there was little wood, in stone. Apart from Duleek (7C), the first stone churches however appear to be the tomb-shrines of founder saints in the 8C, but then in increasing numbers from the 8th -10th centuries. As stone churches these can be recognised by the ‘antae’, that is, flat projecting gable-ends, which imitate upright corner timbers on their wooden predecessors. They had doors in the west (gable) end and sometimes a wonderful doorway made of very large well-dressed stones. As the churches were often small, the people stood outside – outdoor altars being in some cases provided where they could say their prayers. There were perhaps a few larger churches, first in wood, and later in stone.

Many monasteries were built at tribal centres or at meeting places on tribal boundaries. As some monastic communities grew they attracted a resident local community in an arrangement that was of benefit to all. The monasteries provided their spiritual ministrations to local families and taught the children; families helped with the agricultural labour, and with livestock. The dynamic went well – monastery and village grew together. This enabled the monks to take on such great tasks as creating and copying of literature and highly specialised metal-ware. But there were drawbacks. The principal one was that the tribal leader asserted his right to appoint the abbot, who might well turn out to be one of his own family. Worse still, when tribes were involved in a fight, the monks were expected to join in. Then there were the ‘manaim’.

In spite of the fact that the origin of this term and that of the word ‘monk’ is the same these were not the married monks, but men with families who lived round the monastery and who, with their families, lived under considerable religious discipline alongside their spiritual if not natural brothers in the monastery. This included no small degree of sexual abstinence. Any suggestion that these were monks indulging in gross laxity or immorality has to be discounted. Such a life sounds like another of those Irish solutions which had its rationale ‘on the ground’. It is all about finding ‘in-between meanings’. The Irish have always helped us think outside of our boxes – that is very much part of being Irish. Tertiaries in Western monasteries is another ‘in-between arrangement’. In the East married men have always been encouraged to spend time in a monastery.

In time, over 200 years or so, as has often been the case elsewhere, monasteries ran the danger of becoming too big in wealth and power. This led to jealousy, strife and pillage – even from fellow Irishmen. Monasteries were known to have valuables – indeed they were sometimes used as storehouses. But monasteries could also become secularised – especially if tribal leaders expected abbots to have sons in order to keep the monastery in the family. However such a state of affairs, sad though it is, often gave rise to a new impetus for a more genuine monastic life, a simpler, more solitary life, a life more given to prayer and contemplation.

The true ‘holy man’ sometimes put his cell at, or close by, a local place already deemed sacred by the Celts, such as graves, springs, and trees. This gives us some insight into their approach to the native religion and culture. This is of great importance. They did not regard what was there as simply to be destroyed. Rather, just as earlier the Church had seen the Law and Prophets of the Old Testament and Greek philosophy with its ascetic and contemplative culture, so they saw the existing religious culture as a preparation for the Gospel.

In other words the outlook and practices of an existing culture could be given a new shape and direction within the context of the Gospel.

In other words the outlook and practices of an existing culture could be given a new shape and direction within the context of the Gospel.

In the Empire some pagan temples were destroyed and idols smashed. But the situation was different with the Celts. They were not urban temple builders in stone but looked to natural phenomena such as the sun, the sky, the earth, rocks, mountains, water and trees for their deities. Many of their offerings to these have been found in lakes and pits. The days of the seasons were also important to them with regard to continuing fertility and escape from death. Universalised generalisations have to be avoided. But most would agree that the Celts already had some idea of God as three; that they had a very strong sense of creation, awareness of the supernatural and of the unity of things. They had a robust attitude to religious practice; and they believed in a life hereafter.

The early monks and evangelists were able to redirect such sensibilities. Thus the view that saw creation as a manifestation of God could easily be seen as also made by God, and penetrated by his presence.

The early monks and evangelists were able to redirect such sensibilities. Thus the view that saw creation as a manifestation of God could easily be seen as also made by God, and penetrated by his presence.

The Greek and Romans were inclined to work with a dichotomy between matter and spirit. But the Christian belief in Christ the Son of God being born of a woman and uniting himself with humanity gave to the Eastern Fathers a more unitive perception of the divine and the human in the church and in the sacraments and a more cooperative view of their relationship in terms of ‘synergy’ (‘working together’) than was the case in later Western Christianity. In this respect Thom is correct in seeing the early church in Ireland as a ‘Patristic Church’.

The Irish monks showed a great degree of sensitivity to the beauty of creation and God’s presence in it everywhere. Their repentance and asceticism may have been severe by our standards but it was very much motivated by love of God and of one’s neighbour. It is this ‘difference’ from what prevailed in the West which now, by way of reaction, fuels the attraction to ‘all things Celtic’.

It is an interesting comment that ‘the Celtic mind acknowledged no real dichotomy between reality and fantasy, between the world and the ‘world beyond.’ This is precisely what has raised suspicions in people’s minds about the Irish. They may seem at times to blur the edges, to mix the divine and human, to confuse nature and grace – and this is why people call ‘foul’, meaning it is all superstition. I am sure there was confusion and therefore superstition – this will occur in every culture. But this does not mean to say (and here is another fallacy) that the culture is defined by superstition. The church always and without doubt remained very clear as to where the proper lines of demarcation lay between true and false lay and its teaching uncompromised. The conversion of any society is rarely complete..

Two chapters – on holy wells and ancient stones – will consider areas where people have tried to make the accusation of paganism and superstition stick. These are areas where historians are most reluctant to tread because there is more or less nothing in the historical record by which to assess the phenomena. This has created a vacuum in which many have given free reign to strong criticism and wild interpretation.

Irish Hermits and Tomb Shrines

Irish Hermits and Tomb Shrines

The stories of the Desert Fathers have always been compelling reading for the eager monastic disciple the world over. Little by way of literature seems to have escaped the Vikings, but some monastic Rules and several penitentials have survived. Their fierce asceticism however soon cools our ardour. We have to realise these men were tough beyond reckoning. No doubt they were hardy enough to have survived childbirth and youth and the general life-expectancy was not that great. But the tales of endurance, of psalm-singing in freezing waters, and of praying with arms outstretched beyond belief, are enough to convince us that none of us today would have managed. We are not born tough as they were in days of old

On the other hand there must have been times when life seemed good. To sit in the cave of St Colman Macduagh at Keehilla (Co Clare) for any length of time is to discover an altogether different dimension to peace. To look out from St Macdara’s Island (Co Galway), or from Cill Eine (Inishmore, Aran), to the mountains of Connemarra is to indulge in breathtaking beauty. To stay a while on Illauntannig (St Seannach’s island)(Co Kerry) off the north coast of the Dingle Peninsula, with its temperate climate and lovely beach, watching the clouds on Mount Brandon is, as they say, ‘something else’. Even in the north, on Inishkeel, Inishdooey and Tory island, all in Co Donegal (at least on a sunny day) must indeed have seemed ‘like another world’.

The islands on the west coast are such a fascination. Even today they have something of being the ‘Ireland’ beyond Ireland, an ‘Ireland’ more real than that experienced on the mainland. This is not necessarily fantasy – it is, I am told, how some islanders see it. Conditions however out there are such that, while it was possible to live on them for centuries, the battle eventually became too much. We read with great sadness of the moves to the mainland. But then it was feasible for hermits to live out there. The islands are so numerous and so many were colonised. They form as it were a string of pearls weaving in and out from the mainland as on a thread, from Skellig Michael, Inishvickillane, Inishtooskert, Illauntannig, Scattery, the Aran Islands, St Macdara, Omey, High island, Inishbofin, Inishturk, Caher, Clare, Duvillaun, Inishkea south and north, Inishglora, off Belmullet, Inishmurray, Rathlin O’Birne, (and of course Glencolumbkille), Inishkeel, Cruit, Inishdooey, and Tory. They formed a route for the most fervent of pilgrims – and on beyond to the Western isles of Scotland and even to Iceland.

Hermits may not have been fully solitary in the strict sense of the world. Two’s, three’s or even half a dozen may have been more viable. Clusters of hermits over a given area, as happening in the deserts of Nitria and Scete in Egypt, had several advantages. In the Annals one finds even bishops as hermits. If we wish to see something of what the monastic life is about we can do no better than look to them.

The hermit life has often been seen, in the Eastern tradition, as a goal of the monastic life. On the other hand it has stressed very strongly that no one should attempt it without a thorough training and the approval of one’s spiritual father. The life has been called the ‘angelic life’ – as a symbol of the total dependence on God for all one’s needs.

Having said that, a solitary hermit in a cell made of branches left no trace behind him. But saints who depart this life often left disciples who, sensing the saint’s abiding presence, called on their prayers. A little altar might be built over where his body lay and later a little shrine containing his bones. Many of these have been found; they are quite astonishing and they still fill us with awe.

In the Burren, tucked away out of site in a little hollow stands the grave of St Cronan (7C). Of its type it is quite large. It is made of only four pieces of stone, two for the sides, two for the ends, rather like a tent. One end piece is only a half piece – allowing the disciple to put his hand inside and touch the earth where his dear one is buried.

In the early eighth century saints were given their ‘houses’, a small stone edifice where the saint lay. Examples can be found easily at Ardmore for St Declan and at Clonmacnoise for St Ciaran, though that of St Molaise on Inishmurray is probably the earliest. The church on St Macdara’s Island and the one at St Benan’s on Inishmore, Aran are so tiny that only 6 persons can get inside. These too may have been ‘houses’ where disciples could sing God’s praises in the company of their intercessor in heaven.

The Iveragh peninsula seems to have had more than anywhere. Scattered in a vast ring round the peninsula, often looking out to sea, can be found small sites with a bee-hive cell, an outdoor altar and a small tomb-shrine on top of it. Sheer astonishment is experienced when one finds them, sometimes on remote hillsides, sometimes in a field, sometimes on an island, for there they have sat for so long while world history went on its way. What strikes me strongly is how much they are like the hermit sketes of Orthodox monasticism, which I have visited on Mount Athos in Northern Greece.

But the greatest of all was Skellig Michael, on Great Skellig 7 miles out to sea, off the Iveragh Peninsula. Truly this is something else. It takes us beyond words. Our minds are assailed by impossible questions: How did they do it? why did they do it? and for so long. Here nature is at its most awe-inspiring; it is scarcely any place for humans even to venture. What did they live on? How did they survive? The wind, the cold, the Atlantic gales that could blow one away in a trice; and, besides the monastery on the north peak, that hermitage on the south peak at 700 feet, death defying, absolutely unimaginable that it was ever built, let alone manned, – and the loneliness; all these truly terrify, and disturb beyond endurance. Comparisons among the brave are invidious: among Orthodox, the Desert Fathers baked in Egypt, some Syrians lived on pillars, the Russians froze in Siberia; but surely the Irish on Skellig Michael were their brothers.

The eremitic life : Catechism of the Catholic Church

The eremitic life

920 Without always professing the three evangelical counsels publicly, hermits "devote their life to the praise of God and salvation of the world through a stricter separation from the world, the silence of solitude and assiduous prayer and penance."460

921 They manifest to everyone the interior aspect of the mystery of the Church, that is, personal intimacy with Christ. Hidden from the eyes of men, the life of the hermit is a silent preaching of the Lord, to whom he has surrendered his life simply because he is everything to him. Here is a particular call to find in the desert, in the thick of spiritual battle, the glory of the Crucified One.

Nun of Ethiopian Church

920 Without always professing the three evangelical counsels publicly, hermits "devote their life to the praise of God and salvation of the world through a stricter separation from the world, the silence of solitude and assiduous prayer and penance."460

921 They manifest to everyone the interior aspect of the mystery of the Church, that is, personal intimacy with Christ. Hidden from the eyes of men, the life of the hermit is a silent preaching of the Lord, to whom he has surrendered his life simply because he is everything to him. Here is a particular call to find in the desert, in the thick of spiritual battle, the glory of the Crucified One.

Nun of Ethiopian Church

Friday, April 26, 2019

Tuesday, April 23, 2019

Same sex attraction & Gender confusion: SAINTS WHO HELP US ! :)

WOMEN:

Mary, Mother of Jesus :)

St. Teresa of Ávila

St. Mary of Egypt

Sts. Perpetua and Felicity

Ven. Josephata Hordoshevska

St. Bakhita

St. Kateri Tekakwitha

St. Mother Teresa of Calcutta

MEN:

St. Joseph, Husband of Mary :)

St. John of the Cross

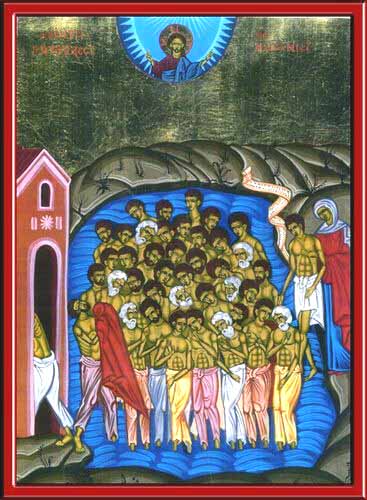

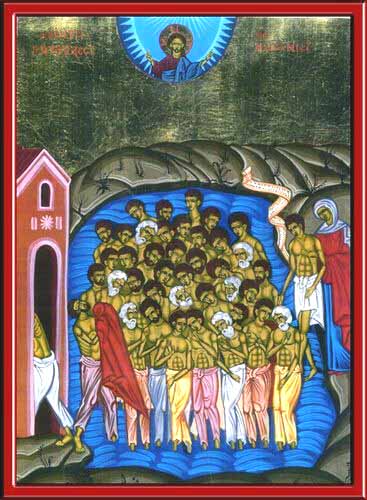

Sts. 40 Martyrs of Sebaste

Ven. Jan Tyranowski

Bl. Isidore Bakanja

Sts. Martyrs of Japan & All Asia

Ven. Joseph Chiwatenhwa and Family

St. Juan Macias, OP

40 Martyrs of Sebaste

Mary, Mother of Jesus :)

St. Teresa of Ávila

St. Mary of Egypt

Sts. Perpetua and Felicity

Ven. Josephata Hordoshevska

St. Bakhita

St. Kateri Tekakwitha

St. Mother Teresa of Calcutta

MEN:

St. Joseph, Husband of Mary :)

St. John of the Cross

Sts. 40 Martyrs of Sebaste

Ven. Jan Tyranowski

Bl. Isidore Bakanja

Sts. Martyrs of Japan & All Asia

Ven. Joseph Chiwatenhwa and Family

St. Juan Macias, OP

40 Martyrs of Sebaste

Saturday, April 20, 2019

Thursday, April 18, 2019

Wednesday, April 17, 2019

Friday, April 12, 2019

Tuesday, April 2, 2019

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)