Resignation of a teacher-Pope

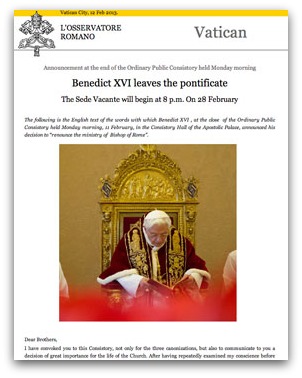

February 12, 2013 Pope Benedict's resignation may be the most significant act of his papacy. It draws attention away from the mystique of popes and bishops, and focuses it firmly on their call to serve the Church.

Pope Benedict's resignation may be the most significant act of his papacy. It draws attention away from the mystique of popes and bishops, and focuses it firmly on their call to serve the Church.His resignation allows us to reflect on his time as Pope. When the Cardinals elected Joseph Ratzinger many Catholics were surprised, and some alarmed at the choice. They identified him with the stern disciplinary actions and doctrinal intransigence of the Congregation for the Defence of the Faith. They assumed he would bring the same narrow focus to his leadership of the Catholic Church.

The reality has been rather different. Certainly, in his approach to the liturgy and in his different attitudes to reactionary and liberal groups on the margins of the Catholic Church, the continuity between the Cardinal and the Pope has been noticeable. But most notable has been the continuing depth and breadth of his reflection.

He has been above all a teacher who can draw richly on Catholic spiritual and theological tradition to illuminate the large social and cultural issues of our day. Over the last decade the Christian world has been blessed by having such reflective and knowledgeable leaders as Pope Benedict and Rowan Williams. For Catholics his resignation will be an opportunity to say thank you to a man who has served the Church faithfully as Pope.

He was a scholar, and to adjust to the constraints and expectations of a public person clearly was not easy for him. His scholarly musings got him into trouble from time to time, but he learned from his mistakes, and finally seemed to derive wry enjoyment from his public engagements, particularly with young people, who responded to his humanity. In his retirement he will surely be looked on with affection and good will.

It is too soon to sum up his achievements and the challenges he leaves to the Church and so to his successor. He grasped the extent and the evil of clerical sexual abuse; dealing with it, and with the aspects of clerical culture that have contributed to it, will occupy the Catholic Church and his successors for the next generation.

Benedict was an acute observer of contemporary culture, particularly of how the focus on technological solutions to problems has pushed aside human values. But his critical analysis in terms of secularism has sometimes encouraged the image of a church in mortal conflict with modern society. Christian engagement with modernity is a continuing and complex story, and we may expect Benedict's successor to bring fresh insights to it.

For the Catholic Church, perhaps Benedict's best gift will turn out to be his resignation. I confess that I had given up on my initial hope after his election as an elderly man that he would resign from his position rather than die in office. He seemed to have the historical grasp and theological breadth required to make this precedent-setting decision, but time was passing.

Given the importance of the papacy in the Catholic Church, the expectation that popes would continue to hold office until death was quite destructive. The increase in life expectancy meant that the cardinals would tend to elect only elderly men because this would be the only way to guarantee change within a reasonable time.

The expectation also meant that during a pope's long decline the principles of good church governance would yield to spiritual snake oil. So John Paul II's suffering during his last years was justified as the heroic acceptance of weakness and a demonstration of the value of the frail and elderly in a society that depreciated them.

The Pope's personal courage and endurance were admirable, and the value of the elderly undeniable. But Popes exist for the good of the Church, and it is difficult to see how the Church's interests are best served by men unable to give full attention to their duties.

So Pope Benedict's resignation is good because it will now allow a circuit breaker for an ageing pope. It will also takes the focus away from the mystique of the Pope to his responsibilities to the church, and will lead to a consideration of what length of tenure by other office holders in the church best serves the church.

Andrew Hamilton is consulting editor of Eureka Street. He is also a policy officer for Jesuit Social Services.

Andrew Hamilton is consulting editor of Eureka Street. He is also a policy officer for Jesuit Social Services.