WHAT ARE ANCHORITES?

by Richenda Fairhurst

Believe it or not, a long time ago, Christian men and women used to literally wall themselves up,sealing themselves into tiny cells attached to churches. They were called Anchorites. They, and their fellows, also lived in caves, next to sacred pools or streams, or in little splintery chapels on islands where the whole idea was to live alone in prayer to worship God unceasingly, and without distraction. Their level of devotion made them holy in their own right, and regular people looked to them for guidance, counsel, and spiritual revelation.

As a group they were called Solitaries. By the middle-ages, the movement was so pervasive and popular that special rites and blessings had evolved to govern the life of the Solitary, which was regulated by the Church. Sometimes Solitaries were monks or nuns. Other times, Solitaries were just very devout princes, princesses, sailors, wanderers, widows, reluctant brides, or whomever was inspired to take up the solitary life.

At first all they needed was a patch of land, the starker (colder, swampier, windier) the better, for endurance in the face of hardship was a key component to their lifestyle. In choosing that land, they had to be careful of the Danes, who could attack and steal their only goat, or the local shepherds, who might get huffy and try to run them off. In later times, Solitaries also needed permission from the landholder and the church.

As a group they were called Solitaries. By the middle-ages, the movement was so pervasive and popular that special rites and blessings had evolved to govern the life of the Solitary, which was regulated by the Church. Sometimes Solitaries were monks or nuns. Other times, Solitaries were just very devout princes, princesses, sailors, wanderers, widows, reluctant brides, or whomever was inspired to take up the solitary life.

At first all they needed was a patch of land, the starker (colder, swampier, windier) the better, for endurance in the face of hardship was a key component to their lifestyle. In choosing that land, they had to be careful of the Danes, who could attack and steal their only goat, or the local shepherds, who might get huffy and try to run them off. In later times, Solitaries also needed permission from the landholder and the church.

Two Kinds of Solitaries

By the middle ages, there were two kinds of Solitaries: Hermits and Anchorites. Hermits were mostly men—though women were hermits, too—who went out into the "desert or wilderness" (though some lived in towns) in order to test their physical fortitude and pray without distraction. They built simple shelters to live in, and simple chapels for worship, sometimes carving them out of stone. They lived on cliffs, in caves, on islands, in swamps, along river shallows, under bridges, anywhere reasonably or very isolated.

The distinction between who was a 'hermit' and who an 'anchorite' was sometimes blurry. In some cases, especially in isolated areas, anchorites were also called hermits. But, in general, an anchorite was usually a person who was specifically walled into a small cell which was attached, or 'anchored,' to a church or oratory.

A 'hermit' sought solitude and also lived in a small cell, but he/she was generally free to come and go. A hermit could farm or hunt for him or herself, while an anchorite was wholly dependent on others to remember to feed them. Both hermits and anchorites were usually sustained through gifts given to them by others (their families, patrons, or passing pilgrims), by tithes from local churches earmarked specifically for their use, or by rights granted to them by the landowner for the use of certain natural resources. A yearly scoop of salmon from the landowner's river, perhaps. Or a yearly sack of grain from the village tithe barn.

The distinction between who was a 'hermit' and who an 'anchorite' was sometimes blurry. In some cases, especially in isolated areas, anchorites were also called hermits. But, in general, an anchorite was usually a person who was specifically walled into a small cell which was attached, or 'anchored,' to a church or oratory.

[Skipton Anchorite Cell. Photo by Immanuel Giel, July 2007.]

A 'hermit' sought solitude and also lived in a small cell, but he/she was generally free to come and go. A hermit could farm or hunt for him or herself, while an anchorite was wholly dependent on others to remember to feed them. Both hermits and anchorites were usually sustained through gifts given to them by others (their families, patrons, or passing pilgrims), by tithes from local churches earmarked specifically for their use, or by rights granted to them by the landowner for the use of certain natural resources. A yearly scoop of salmon from the landowner's river, perhaps. Or a yearly sack of grain from the village tithe barn.

Ironically, Solitaries usually weren't solitary.

Hermits and anchorites attracted followers, pilgrims, and those who needed good spiritual or oracular advice. People flocked to the refuges of the Solitary, sometimes so much so that guest-houses had to be built, farms had to be maintained, and penitents had to be counseled. Too many visitors, however, could drive Solitaries from their cells in search of actual solitude, or force them to shut their windows up and hide out in frustration. One solitary was dragged weeping from his island by a group of his enthusiastic brethren who wanted him to lead them. Yet at other times, Solitaries anticipated and welcomed a steady stream of visitors and would-be associates.

The History: the Eremetic movement of early Christians.

Early Christians flocked to the Egyptian deserts where Copts had already embraced the idea of a solitary, devout Christian life. This early Christians had themselves been inspired by the eremetic traditions of the Hebrews. The idea for these early Christians was to test your ability to deprive yourself—to do without a warm bed, good food, and all the pleasures and comforts of life including companionship. The 'purer' they were, so they believed, the better their chances for eternal life. So many early Christians wanted to imitate Christ's desert experiences and purification, that solitaries could attract great mobs of followers. So many followers could make a cell crowded. To solve the problem, large or small groups of solitaries banded together to create communities, each hermit with their own cell, called Lauras, in the desert. From this beginning, the monastic movement formed.

[Convent of Mar Saba, near Bethlehem. Detroit Publishing Company.]

Many Anchorites were Women.The History: the Eremetic movement of early Christians.

Early Christians flocked to the Egyptian deserts where Copts had already embraced the idea of a solitary, devout Christian life. This early Christians had themselves been inspired by the eremetic traditions of the Hebrews. The idea for these early Christians was to test your ability to deprive yourself—to do without a warm bed, good food, and all the pleasures and comforts of life including companionship. The 'purer' they were, so they believed, the better their chances for eternal life. So many early Christians wanted to imitate Christ's desert experiences and purification, that solitaries could attract great mobs of followers. So many followers could make a cell crowded. To solve the problem, large or small groups of solitaries banded together to create communities, each hermit with their own cell, called Lauras, in the desert. From this beginning, the monastic movement formed.

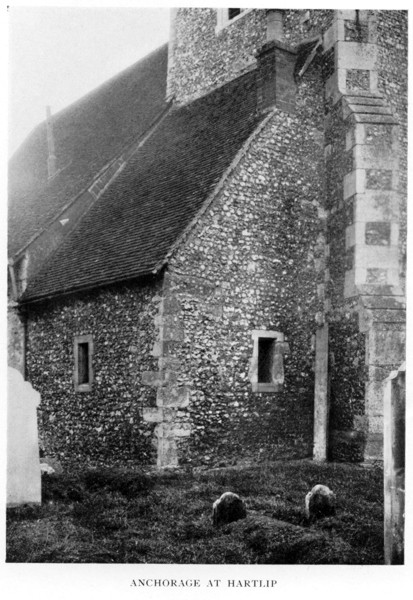

Many more women than men became Anchorites, also called Anchoresses. Women may have been attracted to the life of an anchoress in part because it was a devout and holy job within the church that was actually open to her. Anchorites and Anchoresses literally lived in little rooms called cells built as attachments to a church. Sometimes there was a small door to the cell, often too heavy for the anchoress to move. Other times they were completely walled in except for a window. Inside their cell, the recluse devoted themselves to unceasing prayer.

An anchoress had a higher status than a nun, and was often deferred to by Abbots. In addition to prayer, some anchoresses earned renown as spiritual seers. Anchoresses also embroidered stoles and altar cloths, which were seen as very valuable because of the holy hands who worked it. It was mostly men who worked as book illuminators, though women were known to do that as well.

An anchoress had a higher status than a nun, and was often deferred to by Abbots. In addition to prayer, some anchoresses earned renown as spiritual seers. Anchoresses also embroidered stoles and altar cloths, which were seen as very valuable because of the holy hands who worked it. It was mostly men who worked as book illuminators, though women were known to do that as well.

Anchoresses had to deal with issues of purity that a man did not. Men were not subject to questions of their chastity to the extent that women were (and maybe that was because the general population was already inured to the concept of the philandering monk). The immovable door and the pious personal demeanor were important aspects of her life because they helped prove her virtue. An anchoress could also take up her vocation late in life, choose the solitary life as a widow, or, when young, choose unceasing devotion to escape an unwanted marriage.

Male Hermits and Anchorites often served as Chaplains:

The earliest male hermits were no more than regular men who wanted to chose a holy way of living. Some found a solitary place and stayed put there. Others became wandering hermit-preachers. In the early middle ages, these holy wanderers lived off the land as they went from place to place. But the numbers (and messages) of these independent holy men and women worried the church. Efforts were made to institute some order. By the middle ages, preachers and monks had to be sanctioned by the church. Many of the 'official' Solitaries were men, and of them, most were monks, and of them, many were ordained priests. It was handy to have a Solitary who was a monk and a priest because that Solitary, then, could say Mass, and pray for the souls of brethren and benefactors, at the hermitage chapel.

This is general information. Read more about Hermits and Anchorites in Rotha Mary Clay's The Hermits and Anchorites of England.